What is Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction

Code (BASIC)?

Not an OS, but a complete instruction set

attached to the OS

BASIC (Beginner's All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) was

released in 1964 at Dartmouth College. It was originally designed

as the interactive mainframe time-sharing programming language

for the Dartmouth Time Sharing System (DTSS) OS by Hungarian John

Grorge Kemény (Kemény János György, pictured below) and Thomas

Eugene Kurtz. The original version of the language was later

referred to as Dartmouth BASIC.

.jpg)

For the fiftieth (50th) anniversary of the release of BASIC,

Dartmouth University released a documentary appropriately called

Birth of

BASIC. If you want a quick lesson on computer science

history, I highly recommend it.

For the next three (3) decades or so, BASIC became the de

facto entry-level language for anyone interested in learning

how to control computer systems. The updated version was referred

to a Structured BASIC (SBASIC) in 1975, which became the standard

by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) referred to

Standard BASIC in the early 1980s.

In the late 1970s and throughout 1980s, BASIC was more than

just an entry-level programming language. In tandem with machine

language to control the OS that the manufacturer had included,

BASIC was part of the instruction set for early home computers

like the

TRS-80 Model III running on the ROM-resident TRSDOS and the

C64 running on ROM-resident

KERNAL (misspelling of kernel).

Most importantly, BASIC was the only common factor in personal

computers (8-bit microcomputers, latest technology at the moment)

as binaries were not compatible from one manufacturer to

another.

By today's standards, the late 1970s and most of the 1980s

were strange times when the OS of the machine was not as

important as the manufacturer or the amount of RAM — the more

RAM, the better. We expected the machine to have a built-in a

BASIC interpreter even when we knew that a BASIC dialect might

not be compatible from one manufacturer to another. At the same

time, we were limited to the hardware and software available in

the country or region where the user lived.

For example, vendors and models in the UK were different from

those in the US hence not sold, available or compatible in the US

(PAL instead of NTSC, 50 Hz instead of 60 Hz alternate current).

Because of the relation between England and the rest of the

British Commonwealth, these units were also available in other

countries like Australia and New Zealand.

-

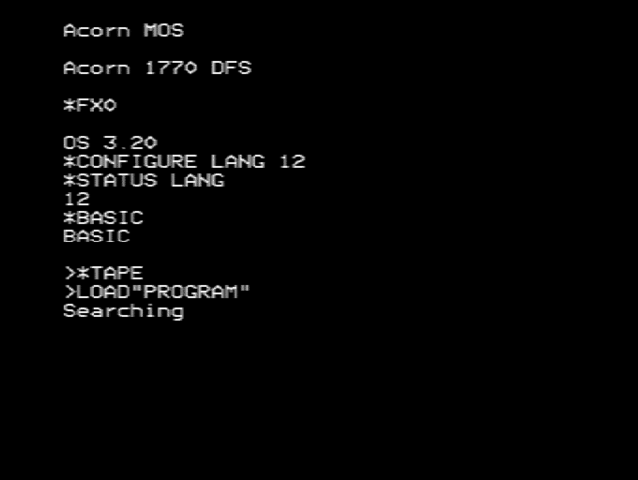

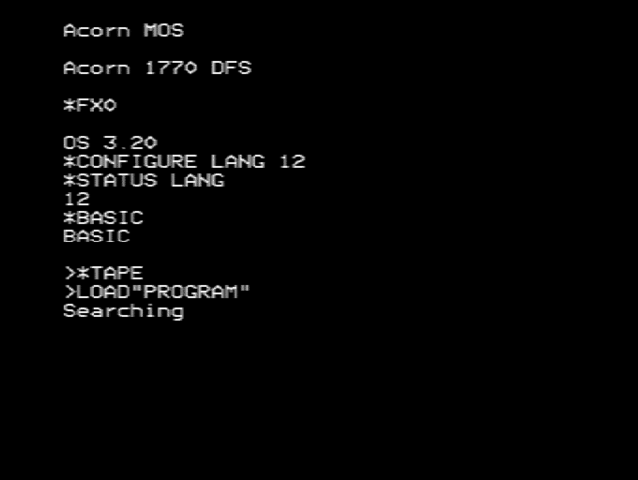

Acorn BBC Micro (1981-94) — Acorn Machine

Operating System (MOS, not to be confused with MOS chips)

with BBC BASIC I, 2 KHz MOS 6502 CPU, 16 KB of RAM; more than

1,500,000 sold

-

Amstrad CPC (1984-90) — Amstrad Disk Operating

System (AMSDOS) with

Locomotive BASIC 1.0, 4 MHz Z80A, 64 KB of RAM, built-in

datassette; 3,000,000 sold

-

Sinclair ZX Spectrum (1983-89) — PCWDOS with

Sinclair BASIC, 3.5 MHz Z80A, 16 KB of RAM; 5,000,000 sold

(1982-92) thanks to a large game library available in

cassettes; produced in the US as Timex Sinclair 2068 (Timex

2068 in the rest of the Americas) with 48 KB of RAM and a

cartridge bay

Probably due to the American market has always influenced

other countries especially English-speaking Canada, in this case,

some vendors and models did arrive at the UK.

-

Commodore 64 (1982-94)

The C64 came with KERNAL (OS) with

CBM BASIC 2.0, a MOS 6202 1.023 MHz (NTSC) or 0.985 MHz

(PAL) and 64 KB of RAM hence C64. More than 15,000,000 were

sold mostly in the US thanks to its large software library

available in ROM cartridges, floppies and cassettes,

peripherals and after-market hardware.

-

Atari 400 (1979-92)

The Atari 400 came with Atari DOS with

Atari BASIC, a MOS 6202 1.79 MHz (NTSC) or 1.77 MHz (PAL) and

8 KB of RAM upgradeable to 16 KB. About 4,000,000 sold thanks

to its large software library available in 8 KB ROM

cartridges.

-

Tandy Color Computer (1980-91)

The TRS-80 Color Computer (1980-83) — nicknamed

CoCo for Color Computer — came with no

DOS, but with MS

Color BASIC (CB) 1.0 (1980) to 1.3 (1982), a 0.89 MHz

Motorola MC6809E and 4 or 16 (later discontinued) or 64 KB of

RAM.

The TRS-80 Color Computer 2 (1983–86) —

later renamed Tandy Color Computer 2 — came with no DOS (optional

Microware OS-9 Level II), but with MS Color BASIC 1.1 (8 KB

ROM) or MS Extended Color Basic (ECB, 1984, 16 KB ROM) or MS

Disk Extended Color BASIC (DECB, 1984) that included

management routines for disks (a heavily stripped-down

version of DOS using

the DOS

command to auto-boot software from disk as in the case

Microware OS-9 Level II with Microware BASIC09 (not BASIC

09), a 0.89 MHz Motorola MC6809E that could be

overclocked to 1.8 MHz by hacking the clock generator, 16 or

32 or 64 KB of RAM and a MC6847T1 video display generator

(VCG) allowing the CoCo to display upper and lower case

characters. The

CoCo 3 with 64 KB of RAM is the system that, if I had not

opted for the C64 in

the spring of 1984, I would have liked to own. Both systems

cost about $300 at the time.

The Tandy Color Computer 3 (1986–91) was

the last model of the CoCo line and no longer referred to as

TRS-80. It came with MS Disk Extended Color BASIC (DECB,

1984) that included routines for disk management (a

stripped-down version of DOS using the

DOS command)

or Microware OS-9 Level II with Microware BASIC09, a 0.895

MHz Hitachi 6309, 128 KB of RAM (upgradeable to 512 KB, 64 KB

dedicated to OS-9), a MC6847 video display generator (VCG)

and a MC6883 synchronous address multiplexor (SAM). The CoCo

3 can run the modern NitrOS9

instead of Microware OS-9.

In all, the CoCo line used four dialects of BASIC.

-

Color BASIC (CB) 1.0 (1980), 1.2 (c. 1981) and 1.3

(1982) by Microsoft

-

Extended Color BASIC (ECB) 1.0 (1984) by Microsoft

-

Extended Color BASIC (ECB) 2.0 (c. 1985) by Microware

after Microsoft's decision not to develop it

-

Disk Extended Color BASIC (DECB, 1984) with routines

for disk management by Microsoft

About 250,000 sold combining all CoCo models (1983–91)

thanks to a large software library available in ROM

cartridges (software packs), floppies and cassettes,

peripherals and after-market hardware. Since the CoCo as well

as its software and its peripherals were made by or solely

sold at Tandy/RadioShack, there was no need for third-party

distribution. The only problem was the decision not allowing

third-parties to develop software for the CoCo, which caused

the quality of some software not be as popular as it could

have been. In other words, sales of CoCo units could have

been ever better.

-

TRS-80 Model I (1977-81)

TRS-80 Model III — nicknamed Trash-80 — came with

TRSDOS 1.3

(optional Logical Systems'

LDOS 5 or NewDos/80) with

Level I BASIC (Steve Leininger, 1977), a 1.774 MHz Z80A and 4

KB RAM expandable to 48 KB.

-

TRS-80 Model II (1979-80)

TRS-80 Model III — nicknamed Trash-80 — came with

TRSDOS with

Microsoft Disk BASIC, 4.00 MHz Z80A and 32 ($3,450) or 64k of

RAM ($3,899).

-

TRS-80 Model III (1980-83)

TRS-80 Model III — nicknamed Trash-80 — came with

TRSDOS 1.3

(optional Logical Systems'

LDOS 5) with Level I BASIC, a 2 MHz Z80A and 4 KB RAM

expandable to 48 KB. Over 250,000 were sold thanks to a large

software library available in floppies and tapes. The TRS-80

was commonly used for work, rather than as a home computer.

As mentioned several times, I used a Model III at school.

-

TRS-80 Model IV (1983-91)

TRS-80 Model III — nicknamed Trash-80 — came with

TRSDOS 6.2 or

Logical Systems' LDOS

6.00, TRSDOS 1.3,

Logical Systems' LDOS

5.3 or Misosys LS-DOS 6.3 or

CP/M 2.2

or 3.0 with Level I or Level II BASIC (Steve Leininger),

4 MHz Zilog Z80A or 6+ MHz with Z80B/Z80H or HD64180/Z180 CPU

configurations. The Model IV was marketed to businesses with

a price of $799 for a disk-less, bare-bones system to $1999

for a double drive unit.

-

Machine with Software eXchangeability

(1983-93)

"Bill Gates demands 100% loyalty and demands being his

subordinate. I'd be very happy to work with him, but I

don't want to sell my soul to him." — Kazuhiko Nishi (Wall

Street Journal, 1986)

MSX was an attempt to standardize hardware so software

written for one system (for example, Toshiba) would work for

another (for example, Hitashi). It was the brainchild of

Kazuhiko Nishi (ASCII Corporation & Microsoft) and Bill Gates

(Microsoft). This meant that there was no need for choosing a

vendor from another with different architectures as software

and peripherals would work on any MSX micro. The MSX

standardization was not a hit in the United States, but Japan

was different. Right after, other markets worldwide followed

— Asia (Korea), South America (Brazil and Chile), Europe

(Netherlands, France, Spain and Finland) and the Soviet

Union.

The common MSX (worldwide, 1983) architecture was based on

a 3.58 MHz Zilog Z80A CPU, at least 8 KB of RAM (most models

shipped with 64 KB), 32 KB of ROM, a General Instrument

AY-3-8910 3-voice programmable sound generator (PSG), 16 KB

of VRAM and a Texas Instruments TMS-9918/9928/9929 video

display processor (VDP) running MSX-DOS with MSX

BASIC 1.0 (based on GW-BASIC with extensions provided by

ASCII).

The common MSX2 (worldwide, 1985) architecture was based

on a 3.58 MHz Zilog Z80A CPU, at least 64 KB of RAM, 48 KB of

ROM, a Yamaha YM2149 PSG, 64 KB of VRAM (most models shipped

with 128 KB), Yamaha V9938 VDP and a Ricoh RP5C01 real time

clock (RTC) chip with a rechargeable battery running MSX-DOS with MSX

BASIC version 2.0 or 2.1.

The common MSX2+ (Japan officially, Europe and Brazil via

upgrades, 1988) architecture was based on a 3.58 MHz Zilog

Z80A CPU (5.37 MHz via software), 64 KB of ROM, at least 64

KB of RAM, a Yamaha YM2149 PSG, at least 128 KB of VRAM, a

Yamaha V9958 VDP and a Ricoh RP5C01 RTC chip with

rechargeable battery running MSX-DOS with MSX

BASIC version 3.0.

The common MSX3 (Japan only, 1988) architecture was based

on a 3.58 MHz Zilog Z80A CPU with 256 KB or a 7.16 MHz ASCII

DAR800-X0G CPU (referred to R800, 28.6 MHz compared to the

Z80) with 512 KB, 96 KB of ROM, a Yamaha YM2149 PSG, at least

128 KB of VRAM, a Yamaha V9958 VDP and a Ricoh RP5C01 RTC

chip with rechargeable battery running MSX-DOS with MSX

BASIC version 4.0.

Computer manufacturers worked around the MSX architecture

to make themselves different from the others — more RAM, more

VRAM, better sound chips, including internal FDDs, including

internal HDDs or any other improvement that could mean better

sales.

I never knew of the MSX architecture or any of these

machines before writing about the different dialects in

BASIC. Coming from the C64 environment, I knew

that computers were obsolete as soon as they hit the shelves

and I had become fairly cynical about new technologies — not

limited to micros, mainframes and midrange computers

too. I am not sure if I would have bought one of a MSX

machines. After all, most MSX machines were not sexy at all —

nowhere near a

CoCo 3. Nowadays I might buy a MSX machine right now out

of curiosity more than anything else — some historical aspect

too.

The 8-Bit War & Me:

I remember reading lots of books on BASIC, machine language

for the C64 and a handful of

copies of BYTE magazine as well as watching TVOntario's

Bits and Bytes on WNET (1983). My experience in junior

high (middle) school was on a disk-less

TRS-80 Model III (1983-85). At home, I spent many hours in

front of my C64

connected to a B/W 13" Zenith TV writing programs that no longer

exist. Saving programs on cassettes was an unreliable yet very

common at the time because it was affordable (about $40) rather

than a floppy disk drive and interface cables for about $250.

I never got a chance to play with an

Atari, a

ZX, a

Amstrad CPC, a

CoCo or any other 8-bit home computer other than my C64.

Maybe this is why I have a fascination with 8-bit computers

specially the

CoCo 3.

Maybe any 8-bit home computer system back then would have been

the same to me, but my first experience with computers was my C64

— not merely a few hours a week in shop class on a

TRS-80 Model III. This is why, on this page, I can only

concentrate on my experience of BASIC on my C64.

Commodore 64 & BASIC 2.0:

The C64 was one of the first computer systems that I ever used

and the first one I ever owned (spring 1984). I quickly got up

hooked into a whole new field and style of life —

geekdom — and coding into late hours of the night

instead of sleeping. The experience of working with KERNAL (the OS), machine language

(accessing KERNAL) and Commodore BASIC

(programming) in its 8-bit glory boasting a 1.023 MHz MOS CPU

Technology 6510 microprocessor and 64 KB of RAM was as fun as it

could be for any kid in the early 1980s. To make things even more

exciting and bringing more curious kids (like me at the time) to

computer science, the C64 was heavily used for games and even

some music programs thanks to its ground-breaking technology

based on two chips by MOS Technology — SIC 6581 and VIC-II.

Commodore International declared bankruptcy and closed shop in

1994.

In 2011, Commodore USA, LLC, took over the Commodore brand

name and released updated versions of the C64 (C64x) with the

same vintage (old, obsolete, ancient, historical, retro)

"breadbox" exterior and VIC 20 (VIC Slim) with their own Linux distribution named Commodore OS. I had

not been thrilled about any new system and/or other technologies

for a long time. The whole idea of reviving the C64x had me like

a little kid before Christmas with a new toy wrapped in front of

him, but I never bought one. Commodore USA closed shop a little

after one of its owners died in 2013.

In 2015, Commodore Business Machines Ltd (UK) took over the

brand name and marketed mobile phones with the C64 look and feel

rather than the classic C64 "breadbox" body.

In 2018, Retro Games Ltd (UK) took over the rights to relive

the heyday of the C64 (1982-85) with The C64 MINI

marketed as a video game console with 64 built-in games and

shipped with its own joystick, THEC64 like the previous

but with a working keyboard as well as a stand-alone joystick

named THEC64 Micro Switch Joystick. The company has also

released new version of the VIC20. All these machines, except for

the stand-alone joystick, can also be used to program Commodore

BASIC (forked from Microsoft BASIC) — the first programming

language that I ever learned. If there was ever a computer I was

excited about its launch, I would say it is the C64. I want to

get my hands on the new the C64, but first I want to make sure

the new Commodore company will last. Needless to say, I am

stoked.

10 INPUT "WHAT'S YOUR NAME? "; NAME$

20 PRINT "HELLO, "; NAME$;

30 INPUT ", HOW ARE YOU? (OK/NOT)" ; OK$

40 IF OK$ = "OK" THEN PRINT "GLAD TO HEAR THAT, "; NAME$; "!"

50 IF OK$ <> "OK" THEN PRINT "TOO BAD, "; NAME$; "! BETTER LUCK NEXT TIME!"

Another nostalgia option was Manomio's licensed emulator for

iOS — iPhone, iPod and iPad. This emulator was almost as

good as the original the C64, but it was removed from the market

without notice. I think someone might have considered it some

sort of copyright violation.

Unfortunately, it has been over three (3) decades since I last

coded my last program for the C64 and I can hardly remember how

to code a quick and dirty (not to mention descent) program

(excluding the one above — OKAY.BAS), but I would

consider it the geekiest purchase I would ever make.

Of course, if you are merely interested in C64 games, you can

get a ROM emulator and a handful of ROM images, which 05/be

illegal in some areas and/or under special conditions as

explained in

17 U.S.C. § 117(a).

§ 117 . Limitations on exclusive rights: Computer

programs

(a) Making of Additional Copy or Adaptation by Owner of

Copy.—Notwithstanding the provisions of

section 106, it is not an infringement for the owner of a

copy of a computer program to make or authorize the making of

another copy or adaptation of that computer program

provided:

(1) that such a new copy or adaptation is created as an

essential step in the utilization of the computer program in

conjunction with a machine and that it is used in no other

manner, or

(2) that such new copy or adaptation is for archival purposes

only and that all archival copies are destroyed in the event

that continued possession of the computer program should cease

to be rightful.

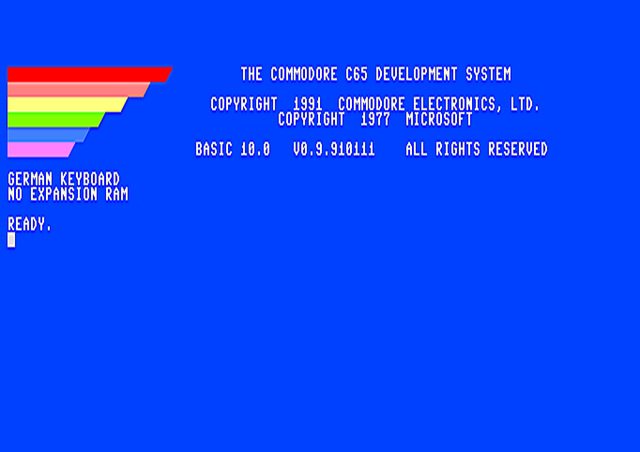

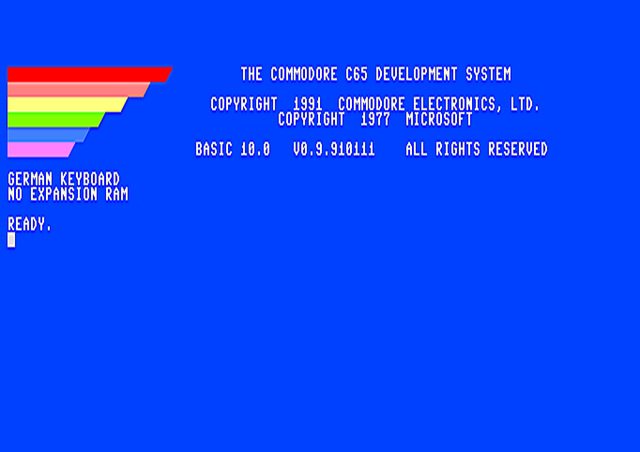

In 1990 or 1991, Commodore came up with a prototypes

for the Commodore 65 (probably just a prototype name). Being a

prototype, only few units exist and one of these units could

easily sell in an auction for close to 47,000€ (about $49,500).

The C65 boasted a 3.54 MHz 16-bit CSG 4510 CPU (compared to the 1

MHz CPU in C64) combined with two MOS 6526 chips, Universal

Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART) serial interface, 1 MB

of RAM mapping (depending on RAM expansion), a VIC-III graphics

chip (256 colors, 40/80×25 text), CSG 8580R5 SID chips capable of

independent outputs (stereo), 128 KB of RAM built-in (1 MB

maximum via an expansion port), CBM-BASIC 10.0 (not version 2.0

as in the C64) and built-in 3.5" double-sided disk density (DSDD)

floppy disk drive accessible via DOS (not the

controller for the external floppy disk drive as in the C64).

The Museum of Electronic Games & Art (MEGA,

Germany) is producing the MEGA65 with a 40.5 MHz 8-bit GS4510 CPU

(about the same speed as an i486 though not sure of the vendor of

the new CPU), 384 KB of fast RAM (old CBM hardware) and 8 MB of

Hyper-RAM (hypervisor), four soft-SIDs and two 8-bit DACs

(digital-to-analog converters), MEGA OS (hypervisor to run

multiple VMs: BASIC 10 or BASIC 65

GEOS 64 or Contiki) on a VFAT32 formatted SD. The latter

comes as a DevKit (development kit; in other words, parts for the

user to build) of the C65 for

666.66€ or 793.33€ gross (about $705 or $835 gross). Maybe the

MEGA65 is sold as a kit to lower costs or to avoid legalities. In

either case, this kit is for anyone with a background in

computers and programming including assembly. It seems that the

only difference between the MEGA65 and the original C64 is the

ability to access SD cards (disk images including KERNAL and the BASIC ROM files)

rather than only 3.5" floppies and the introduction of Computer Based Disk

Operating System (CBDOS) and BASIC 10

(just like the C65

prototype) and BASIC 65. This means that the MEGA65 can run in

three different modes — BASIC 2.0 (C64.ROM), BASIC 10

(C65.ROM) and BASIC 65 (MEGA65.ROM).

Note that, since the MEGA65 is made in Germany, the output

might be PAL (50 Hz AC, 625 lines, 50 fields, 25 fps) and might

not work on NTSC (60 Hz AC 625 lines, 60 fields, 30 fps). I could

not find this in the system specifications (specs). If you have a

dual mode monitor, you should be okay.

TRS-80:

As I mentioned before, I also have a special memory of the

TRS-80, specially Model III and the Color Computer 3 (CoCo 3) —

not other models of the TRS-80 family. I used a TRS-80 at school

(two students per machine). I enjoyed annoying others with the

orange button on the top right hand side of the keyboard — memory

flush, similar to the NEW command in BASIC (Level I

BASIC, in this case).

.jpg)

I never used a

CoCo 3, but I remember seeing it in Radio Shack stores and

thinking that it was a sexy machine. As a matter of fact, the

CoCo 3 remains as one of the sexiest computers ever made.

![By Lamune (Talk) — Copyed from English Wikipedia Tandycoco2.jpg], Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=460962 By Lamune (Talk) — Copyed from English Wikipedia Tandycoco2.jpg], Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=460962](/img/320px-TRS-80_Color_Computer_2-64K.jpg)

Other Versions of BASIC:

There are many versions (dialects) of BASIC. The following is

a quick list of interpreters in chronological order.

-

Microsoft BASIC originally released as Altair BASIC for

Altair 8800 (1975)

-

Integer BASIC (Apple BASIC) for Apple I and Apple II

(1977)

-

Commodore BASIC (PET BASIC or CBM-BASIC) from PET

(ver. 1.0, 1977) to C128 (ver. 7.0, 1985) — the dialect that

got started as a programmer in spring 1984 on the C64 running version

2.0

-

Color BASIC for TRS-80 CoCo (1980-91)

-

BASIC Programming ROM cartridge (Warren Robinett, 1979),

replaced with Atari Microsoft BASIC for Atari 8-bit home

computers sold on floppy and ROM cartridge under the name

Atari Microsoft BASIC II (Microsoft, 1981-92) IBM BASIC

available as Cassette BASIC, Disk BASIC and Advanced BASIC

(BASICA) for IBM 5150 (1981) and Cartridge BASIC for IBM PCjr

(1984)

-

Modern versions of BASIC

-

Visual Basic (Microsoft, 1991) for Windows only

-

Liberty BASIC (Carl Gundel, Shoptalk

Systems, 1992), followed by Run BASIC (2008) that is a

web application server running the Liberty BASIC and

SQLite versions released that year — only release, no

updates

-

Gambas (Benoît Minisini, 1999) for

Unix-like environments

only

-

Visual Basic .NET, also referred to as

VB.NET (Microsoft, 2001) for Windows only

-

FreeBASIC (Andre Victor, FreeBASIC

Development Team, 2004)

-

Mono (Miguel de Icaza under Ximian, then

.NET Foundation and Xamarin, 2004) to port VB.NET to

Linux

-

Small Basic (Microsoft, 2008) for

Windows only

-

SmileBasic (SmileBoom Co. Ltd, 2011)

for children to program games for the Nintendo 3DS

console

-

True Basic (John Kemény, Thomas Kurtz,

1983) made by the authors of the "original"

BASIC at Dartmouth College (1964), for Windows and macOS

-

TinyBasic (Tom Pittman, 1976) made as a

result of "a lot of whining about Bill Gates charging

$150 for his Basic interpreter" (Jul 2004)

-

Xojo (Xojo, 2020)

Installing BASIC:

BASIC on i286 and prior machines came burnt to a ROM chip.

There is no way users could install BASIC other than changing the

ROM chips. On boot, it loads from the built-in ROM to RAM. Later

machines would run DOS

and have BASIC as a stand-alone executable like

QBASIC.EXE (Microsoft BASIC), but by no means being the

similar instruction set of the late 1970s or 1980s.

Nowadays there are newer versions of BASIC that are installed

as any other program would be on a computer via an executable or

script. For example, FreeBASIC is available for DOS, Windows and Linux.

No More BASIC, 16-Bit Microcomputers:

When 16-bit computers became mainstream in the late 1980s,

BASIC was no longer intertwined with the OS and programming no

longer was the main purpose of computers. In most OSs, BASIC was

just reduced as a stand-alone binary like GW-BASIC (numbering

each line, Microsoft, 1983-88) or QBasic (structured programming,

Microsoft, 1991-present). Slowly BASIC was removed from OS

distributions like Windows.

The BASIC Love Affair with 8-Bit Micros:

Most nerds (myself included) who grew up with micros

(1977-95) love these machines. More than nostalgia, it is a love

affair or even a sub-culture (cult, as in cultural).

This is the reason why there is a whole market of second-hand

8-bit micros and modern hardware that can be connected

to the old hardware like HDDs and FDD emulators, hardware

replacement and upgrades to bypass the original like sound and

video cards, wireless adapters, PAL to NTSC converters and such.

As a matter of fact, Tandy/RadioShack, Commodore, Atari, Acorn

and Sinclair micros (including non-licensed USSR clones)

are some of the best selling units in the second-hand market

(eBay, etc.) with prices ranging from $100 to $500 bare-bones.

Even 16-bit micros like the line of Commodore Amiga can

easily sell from $200 to $1,000. Software, original monitors and

peripherals can also demand high prices depending on manufacturer

and rarity. Brand new (never open, often referred to a new old

stock) vintage machines can sell for thousands. Of course, these

prices are usually for mass-produced micros. Prototypes like

C65 can demand 47,000€

(about $49,500) in auction.

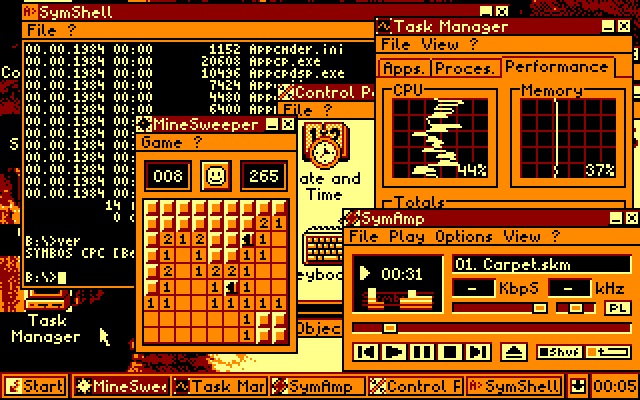

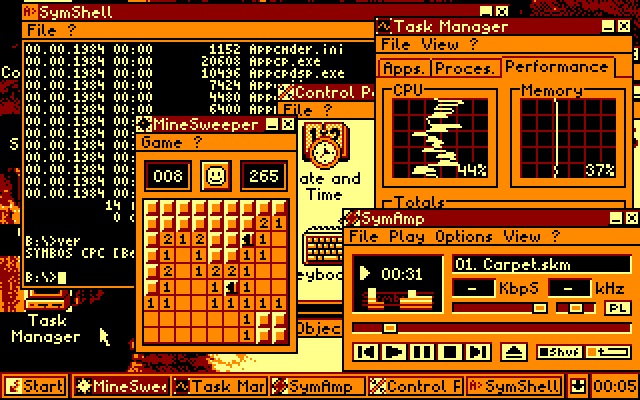

Z80 & SymbOS:

Most 8-bit micros ran on the Zilog Z80 CPU

architecture, which hit the market in 1976. In 2006, German

developer Jörn "Prodatron" Mika released SymbOS. The latter is a

multitasking OS that runs on Z80 chips as replacement to the

built-in OS of a given computer with a GUI similar to Windows 95 written in

assembly.

.jpg)

.jpg)

![By Lamune (Talk) — Copyed from English Wikipedia Tandycoco2.jpg], Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=460962 By Lamune (Talk) — Copyed from English Wikipedia Tandycoco2.jpg], Copyrighted free use, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=460962](/img/320px-TRS-80_Color_Computer_2-64K.jpg)